Can the Polio Virus Kill Brain Tumors?

February 10, 2020

UH one of 4 sites participating in Phase II clinical trial

Innovations in Neurology & Neurosurgery | Winter 2020

Andrew E. Sloan, MD, FACS

Andrew E. Sloan, MD, FACSPolio has been eradicated in the Americas since 1994. Why would researchers intentionally use the virus to treat patients with brain tumors?

University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center is one of only four sites participating in a Phase II clinical trial to test the safety and efficacy of oncolytic polio/rhinovirus recombinant (PVSRIPO), a modified polio virus, in patients with recurrent malignant glioblastoma (GBM).

The Phase I trial, conducted at The Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke Cancer Institute, showed encouraging results. Overall survival among patients who received PVSRIPO plateaued at 21 percent at 24 to 36 months and appears to last for up to five years. The overall survival rate was sustained at 36 months in these patients.1

A 21 percent survival rate may not sound like good news. However, patients with recurrent malignant glioblastoma, an aggressive primary brain tumor, have a median survival rate of only about one year.2 Currently, only about 2 percent of patients survive two years. The needle hasn’t moved since the 1980s.

“We’ve never seen survival rates like this before,” says Andrew E. Sloan, MD, FACS, Director of the Brain Tumor & Neuro-Oncology Center and the Center of Excellence in Translational Neuro-Oncology at University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center and University Hospitals Neurological Institute, and Professor and Vice Chairman, Department of Neurosurgery at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, who serves as principal investigator for the trial. “The long-term survival rate is very exciting.”

In May 2016, the Food and Drug Administration granted PVSRIPO breakthrough therapy designation, which expedited research. It also garnered the therapy attention on the television news program 60 Minutes.

Because of UH Cleveland Medical Center’s significant brain tumor program, immunotherapy expertise and experience as a research center, trial sponsors Istari Oncology and Duke University chose University Hospitals as one of a select number of research sites for the Phase II study. Participation involves physicians and staff from UH Neurological Institute and the School of Medicine’s Oncology Department and clinical research units.

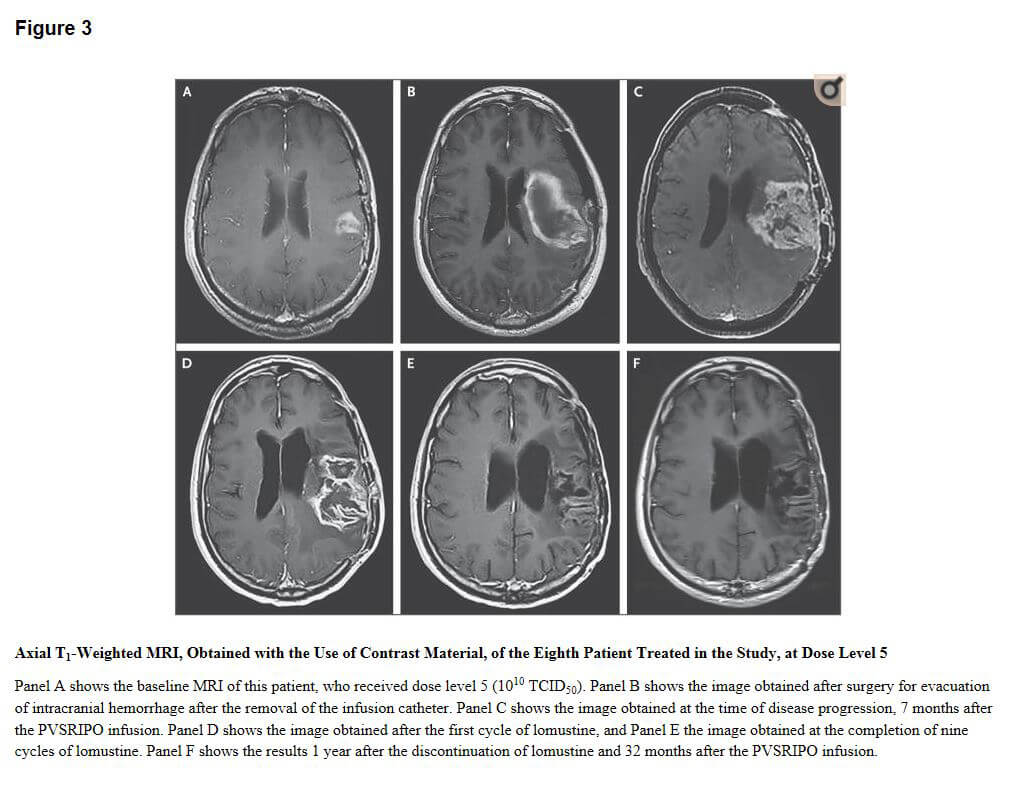

Figure 3 credit: Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon JE 2nd, et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Recombinant Poliovirus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):150–161. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1716435.

Figure 3 credit: Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon JE 2nd, et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Recombinant Poliovirus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):150–161. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1716435.How the Polio Virus Kills Tumors

Neuro-oncologist Robin Buerki, MD, MPhil, Assistant Professor, Department of Neurology at the School of Medicine, and member of the Developmental Therapeutics Program at Case Comprehensive Cancer Center at the School of Medicine, explains that the poliovirus infects and enters cells by binding to CD155, a protein on the surface of certain cells.

Glioblastoma cells have high levels of CD155. Duke molecular biologist and neurosurgery professor Matthias Gromeier, MD, modified the polio virus to remove the genetic sequence targeting neurons. The modified virus replicates only in glioblastoma cells, not in normal cells.

“When the modified virus attaches to the tumor cells, it triggers an immune response in the body,” says Dr. Buerki. “That causes an inflammatory response, which attacks and destroys the tumor.”

Physicians will use convection-enhanced delivery to administer PVSRIPO directly to the tumor site through a surgically implanted catheter. There is no placebo group.

The primary goal is to measure 24-month survival rate after PVSRIPO administration. Researchers will also measure adverse events, inflammatory reaction and immunologic changes.

“The advantage of immunotherapy approaches such as the polio virus is that they not only attack the tumor at the time the drug is given, but create ‘immunological memory’ so the treatment only needs to be given once to train the immune system to attack the tumor,” Dr. Sloan says.

“When you get a polio shot, you won’t get polio for the rest of your life,” Dr. Buerki adds. “With this therapy, we hope patients become inoculated against the tumor in the same way.”

The PVSRIPO clinical trial is recruiting patients at University Hospitals. To learn more about the study, reference NCT02986178.

You may also contact Christopher Murphy, RN, Clinical Research Nurse Specialist, University Hospitals for information at 216-553-1778.

References

1. Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon JE 2nd, et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Recombinant Poliovirus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):150–161. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1716435. Accessed at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6065102/

2. Walid MS. Prognostic factors for long-term survival after glioblastoma. Perm J. 2008;12(4):45–48. doi:10.7812/tpp/08-027. Accessed at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3037140/