Sleep, Obesity and Cardiovascular Health

August 29, 2021

UH physicians seek new ways to intervene and prevent obstructive sleep apnea

Innovations in Pulmonary & Sleep Medicine | September 2021

A bidirectional relationship exists between obesity, sleep and cardiovascular health. Ian J. Neeland, MD, FAHA, FACC is pursuing a grant to fund research to learn more about what physicians might do clinically to intervene and prevent obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Ian Neeland, MD, FAHA, FACC

Ian Neeland, MD, FAHA, FACC Kingman Strohl, MD

Kingman Strohl, MD“OSA is strongly related to obesity,” says Dr. Neeland, Director of Cardiovascular Prevention at University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute. “In fact, it’s the biggest risk factor for OSA."

“We originally believed OSA was related to anatomical traits, such as fat in the neck or having a short neck,” he adds. “However, more recent research finds non-anatomical physiological traits of OSA as well, such as ventilatory control problems and muscle hyporesponsiveness. We believe there is a connection between these traits. This is really an emerging concept and state of the art in sleep medicine.”

Treating OSA

Understanding the links is important, of course, but finding successful interventions for OSA is the goal. To that end, a new class of drugs — sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors — may be an effective intervention, says Kingman Strohl, MD, an internationally renowned sleep expert collaborating with Dr. Neeland on the research. Dr. Strohl is Director of the Sleep Medicine Fellowship Program at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

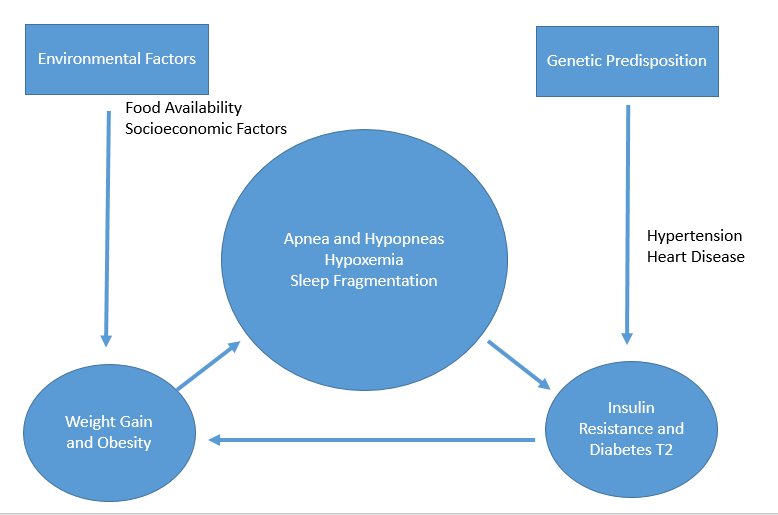

Sleep apnea may lead to an increase in insulin levels, which is a fundamental part of diabetes pathogenesis, Dr. Strohl says. Increased insulin leads to weight gain, which increases the tendency to develop sleep apnea.

“The intervention proposed by Dr. Neeland has two parts,” Dr. Strohl says. “First, we want to know if SGLT2 inhibition starts to affect sleep apnea before there is significant weight loss. Second, can we detect the causal mechanisms for this drug effect? Looking forward, could we conceive of a medication to prevent people with diabetes and incipient obesity from developing sleep apnea? This is a very innovative line of research.”

It turns out, the SGLT2 inhibitor Empagliflozin (Jardiance) appears to help.

“Empagliflozin is used to lower blood sugar in adults with type 2 diabetes and to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death in these patients,” Dr. Neeland says. “We found it cut the risk for sleep apnea in half, although it had only a modest effect on weight loss, not enough to explain the lower risk for OSA.

“We want to know how Empagliflozin influences metabolism and organ systems,” he adds. “Part of our proposed study will delve into this with a mechanistic clinical trial in which we’ll randomize patients with obesity and sleep apnea to the drug or placebo and measure all the anatomic and non-anatomic traits using state-of-the-art MRI imaging and home sleep study equipment.”

The other part of the study is to look at sleep deficiency as a larger construct in the Dallas Heart Study. This is a large epidemiologic cohort study with 2,000+ people to look at sleep deficiency.

“We’re hoping this grant gets funded,” Dr. Neeland says. “It highlights our understanding of the emerging links between obesity, heart disease, sleep deficiency and sleep apnea.”

Dr. Strohl is pleased that cardiologists are now working with sleep experts on chronic risk factors and new modifications affecting both cardiac and OSA risk.

“It may be an important risk factor for cardiologists to worry about,” he says, “and they’re now working with sleep experts on this issue. There may be other areas where this is also important, such as chronic renal disease.”

Screening is key

In the meantime, Drs. Strohl and Neeland encourage clinicians to screen patients, especially those who are obese, for sleep issues, such as daytime sleepiness and snoring at night. Several easy and widely used screening tools — such as STOP-BANG (which stands for snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, high blood pressure, BMI, age, neck circumference and male gender) and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, which assesses subjective daytime sleepiness — make screening easy.

“If a patient is at risk, it’s worth taking a second look,” Dr. Neeland says. “Undiagnosed sleep apnea or sleep disorders increase the risk for heart disease, pulmonary hypertension and makes blood pressure more difficult to control. It’s a vicious cycle: sleep apnea feeds into obesity, so patients sleep and exercise less and eat more.

“UH has specialists who deal with this. We have a comprehensive sleep lab and are also doing weight loss studies. Know there are resources out there for your patients.”

UH is also providing advanced clinical care of diabetes patients through the Center for Integrated and Novel Approaches in Vascular-Metabolic Disease (CINEMA), a multidisciplinary program of UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute. The care includes a diabetes educator, nurse navigator and a cardiologist who is proficient in diabetes care.

“We’ve been making amazing strides with patients, lowering blood pressure and cholesterol and improving blood sugar control,” says Dr. Neeland, who is Co-Director of CINEMA. “If you have complex patients, it’s a great opportunity to refer them to CINEMA.”