Congenital Heart Disease

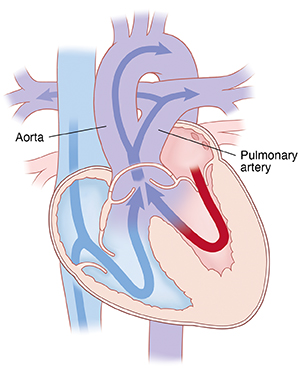

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a problem that occurs as the baby's heart is developing during pregnancy, before the baby is born. This is the most common type of birth defect.

A baby's heart starts to develop at conception. But it is fully formed by 8 weeks into the pregnancy. Congenital heart defects happen in the first 8 weeks of the baby's development. Certain steps must take place for the heart to form correctly. Often congenital heart defects occur because 1 of these steps doesn't happen at the right time. For example, a hole is left where a dividing wall should have formed. Or a single blood vessel is formed where 2 should have been.

What causes congenital heart disease?

Most congenital heart defects have no known cause. Mothers will often wonder if something they did during the pregnancy caused the heart problem. In most cases, no cause can be found. Some heart problems do occur more often in families. So there may be a genetic link to some heart defects. Some heart problems are likely to occur if the mother had a disease while pregnant. Or they may occur if she was taking certain medicines, such as antiseizure medicines or the acne medicine isotretinoin. But most of the time, there is no clear reason for the heart defect.

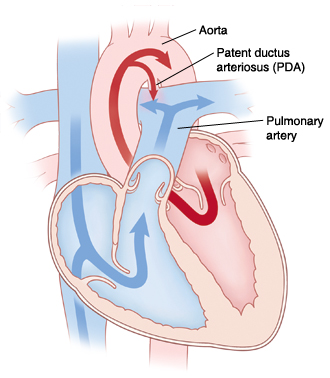

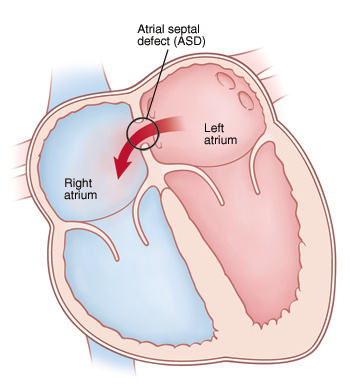

Congenital heart problems range from simple to very complex. Some heart problems can be watched by the baby's healthcare provider and managed with medicines. Others will need surgery. In some cases, surgery is done in the first few hours after birth. A baby may even grow out of some of the simpler heart problems. These include patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or atrial septal defect (ASD). These defects may simply close up on their own with time or growth. Other babies will have a mix of defects. They will need several surgeries during their lives.

What are the different types of congenital heart defects?

Experts group congenital heart defects into several categories. This helps to better understand the problems the baby will have. They include:

-

Problems that cause too much blood to pass through the lungs. These defects let oxygen-rich blood that should be traveling to the body recirculate through the lungs. This causes more pressure and stress in the lungs.

-

Problems that cause too little blood to pass through the lungs. These defects allow blood that has not been to the lungs to pick up oxygen (oxygen-poor blood) to travel to the body. The body does not get enough oxygen with these heart problems. The baby may have a blue color (cyanosis).

-

Problems that cause too little blood to travel to the body. These defects are due to underdeveloped heart chambers or blockages in blood vessels. This prevents the correct amount of blood from going to the body to meet its needs.

Again, in some cases there will be a mix of a few heart defects. This creates a more complex problem that can fall into a few of these categories.

Some of the problems that cause too much blood to pass through the lungs include:

-

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). As babies develop in the uterus, they get oxygen-rich blood from the placenta. The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel that allows the blood to bypass the lungs and go directly into circulation. This changes after birth when the umbilical cord is cut. A baby's first breath starts the process of opening the vessels in the lungs so that the baby can oxygenate its own blood. The PDA defect occurs when the normal closure of the ductus arteriosus, which is present in all babies, does not occur. Extra blood then goes from the aorta into the lungs. This may lead to flooding of the lungs, very fast breathing, and poor weight gain. PDA is often seen in premature babies.

-

Atrial septal defect (ASD). In this condition, there is a hole between the 2 upper chambers of the heart (the right and left atria). This causes an abnormal blood flow through the heart. Some children may have no symptoms and look healthy. But if the ASD is large, then much more blood will pass to the right side. Then there will be symptoms. This causes extra blood to be pumped into the lungs by the right ventricle. This can create congestion in the lungs.

-

Ventricular septal defect (VSD). In this condition, there is a hole in the ventricular septum. This is a dividing wall between the 2 lower chambers of the heart (the right and left ventricles). Because of this opening, blood from the left ventricle flows back into the right ventricle, due to higher pressure in the left ventricle. This causes extra blood to be pumped into the lungs by the right ventricle. This can create congestion in the lungs and strain on the left side of the heart.

-

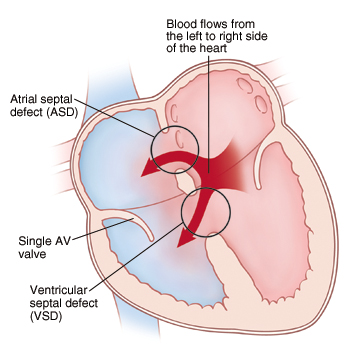

Atrioventricular canal (AVC or AV canal). AVC is a heart problem that includes several abnormalities of structures in the heart. These include ASD, VSD, and incorrectly formed mitral or tricuspid valves. The mitral and tricuspid valves are the valves that separate the upper chambers (atrias) from the lower chambers (ventricles). They help keep blood flowing forward in the right direction. Often this defect causes extra blood to be pumped into the lungs by the right ventricle. This can create congestion in the lungs.

Some of the problems that cause too little blood to pass through the lungs include:

-

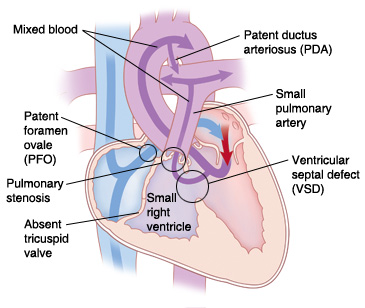

Tricuspid atresia. In this condition, the tricuspid valve does not form. So no blood flows from the right atrium to the right ventricle. Tricuspid atresia is marked by the following:

-

A small right ventricle

-

Poor blood flow to the lungs

-

A blue color of the skin and mucous membranes caused from a lack of oxygen (cyanosis)

A series of surgeries is often needed to increase the blood flow to the lungs and create separate circulations.

-

-

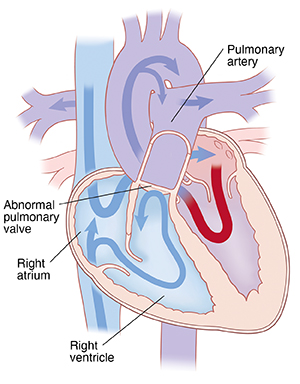

Pulmonary atresia. With this condition, the pulmonary valve or artery are not fully developed. Normally, the pulmonary valve is between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. A normal functioning pulmonary valve has 3 leaflets that work like a 1-way door. They let blood flow forward into the pulmonary artery. But they don't let it flow backward into the right ventricle. With pulmonary atresia, problems with valve development stop the leaflets from opening. So blood can't flow forward from the right ventricle to the lungs.

-

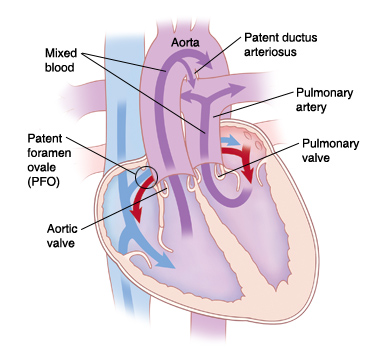

Transposition of the great arteries. The positions of the pulmonary artery and the aorta are reversed. In this defect:

-

The aorta starts from the right ventricle. So most of the oxygen-poor blood returning to the heart from the body is pumped back out without first going to the lungs.

-

The pulmonary artery starts from the left ventricle. So most of the oxygen-rich blood returning from the lungs goes back to the lungs again.

-

-

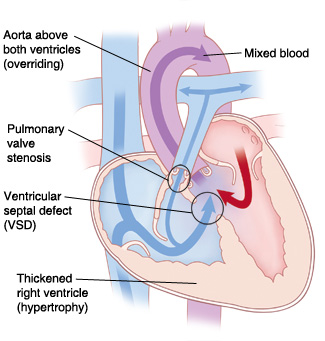

Tetralogy of Fallot. This condition is marked by these 4 defects:

-

A ventricular septal defect. This lets blood pass from the right ventricle to the left ventricle without going through the lungs.

-

A narrowing (stenosis) at, or just under, the pulmonary valve. This partly blocks blood flow from the right ventricle to the lungs.

-

Thickening or enlargement of the right ventricle.

-

The aorta lies right over the ventricular septal defect (called an overriding aorta).

Tetralogy of Fallot can cause a blue color of the skin and mucous membranes due to lack of oxygen (cyanosis).

-

-

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV). Normally, the aorta connects to the left ventricle. With this complex condition, both the aorta and the pulmonary artery are connected to the right ventricle. This causes oxygen-poor blood to circulate in the body.

-

Truncus arteriosus. During a baby's normal development, the aorta and pulmonary artery start as 1 blood vessel. Then the vessel divides into 2 separate arteries. Truncus arteriosus occurs when the single large vessel doesn't fully separate. This leaves a large connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

Some of the problems that cause too little blood to travel to the body include:

-

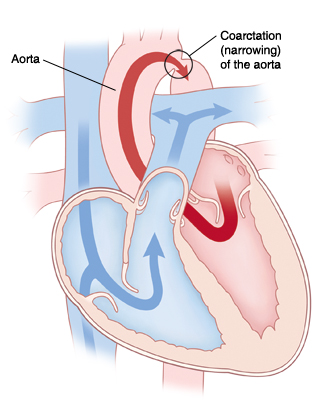

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA). In this condition, the aorta is narrowed or constricted. This blocks blood flow to the lower part of the body. And it increases blood pressure above the constriction. Often there are no symptoms at birth. But symptoms can occur as early as the first week of life. If there are severe symptoms of high blood pressure and congestive heart failure, surgery will be needed.

-

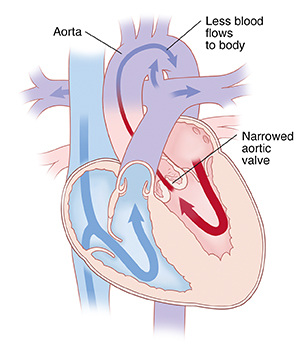

Aortic stenosis (AS). In AS, the aortic valve between the left ventricle and the aorta did not form correctly and is narrowed. This makes it hard for the heart to pump blood to the body. A normal aortic valve has 3 leaflets (cusps). But a stenotic valve may have only 1 cusp (unicuspid) or 2 cusps (bicuspid). Aortic stenosis may not cause symptoms. But it may get worse over time. Surgery or a catheterization procedure may be needed to fix the blockage. Or the valve may need to be replaced with a manmade one.

A complex combination of heart defects known as hypoplastic left heart syndrome can also occur.

-

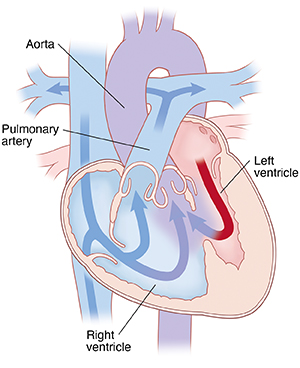

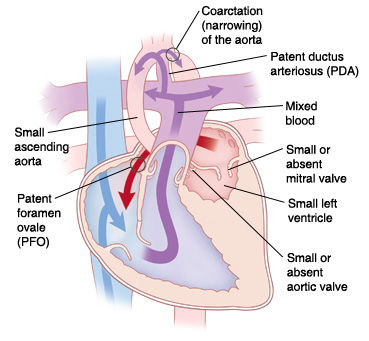

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). A combination of several abnormalities of the heart and the great blood vessels. In HLHS, most of the structures on the left side of the heart (including the left ventricle, mitral valve, aorta, and aortic valve) are small and underdeveloped. How underdeveloped they are will be different for each child. The left ventricle may not be able to pump enough blood to the body. HLHS is fatal without treatment.

Who treats congenital heart defects?

Babies with congenital heart problems are cared for by specialists called pediatric cardiologists. These healthcare providers diagnose heart defects. And they help manage a child's health before and after surgery to fix the heart problem. Specialists who fix heart problems in the operating room are pediatric cardiovascular or cardiothoracic surgeons.

Today, people with congenital heart disease (CHD) are living longer. The number of adults with CHD is now greater than the number of babies born with CHD. This improved survival rate is due to major advances in tests, treatments, and surgical methods.

Children with CHD who reach adulthood must move (transition) from pediatric care to adult cardiac care. This is vital if they are to reach and maintain the highest level of wellness. The type of care needed is based on the type of CHD a person has. Those with simple CHD can often be cared for by a community adult cardiologist. Those with more complex types of CHD must be cared for at a center that specializes in adult CHD.

Adults with CHD have different needs and concerns than children. Adults with CHD need guidance for planning key life issues such as:

- College

- Career

- Employment

- Insurance

- Activity

- Lifestyle

- Inheritance

- Family planning

- Pregnancy

- Chronic care

- Disability

- End of life

Knowledge about certain CHDs, and expectations for long-term outcomes and possible problems and risks, must also be reviewed. This is part of the successful move from pediatric care to adult care. This transition starts in your child's early teen years. During this first phase, both you and your child's specialist should talk about your teen one day being responsible for their own care. This will depend on several factors, such as your child's ability to care for themselves. It's best to start talking about this when your child is fairly healthy. Your child will need to be able to:

- Talk in some detail about their condition

- List their medicines and when they take them

- Tell if their condition is changing or getting worse

Helping your teen transition to adult cardiac care

As a parent, you must help your young teen get ready to transition to adult cardiac care. Make sure your child knows the details of their condition and their medicines. Help them understand they must start to take control of their care as a young adult. This will help ensure a smooth transition to adult care. And it will help ensure the best possible health outcomes for your child as a young adult with CHD. Talk with your child's pediatric cardiologist about how to make the change from pediatric to adult providers. Here are some things to think about:

-

Ask your child’s healthcare team when they typically move children to adult clinics.

-

Ask the healthcare team for advice in finding qualified healthcare providers.

-

Plan for changes in insurance.

-

Understand the psychological challenges that can occur when teens move to an adult practice. They may feel nervous, excited, hopeful, and frustrated. It's important for the teen to have someone besides a family member to talk with. They can discuss how their disease may affect dating and other social relationships.

-

Work with your pediatric clinic to make a list of goals for this move. Check on these goals at each routine visit.

-

Talk with your child early and often about their role as a patient. Taking a greater role in their own care over time is a big responsibility. Give positive reinforcement when your child shows independence in managing their own healthcare.