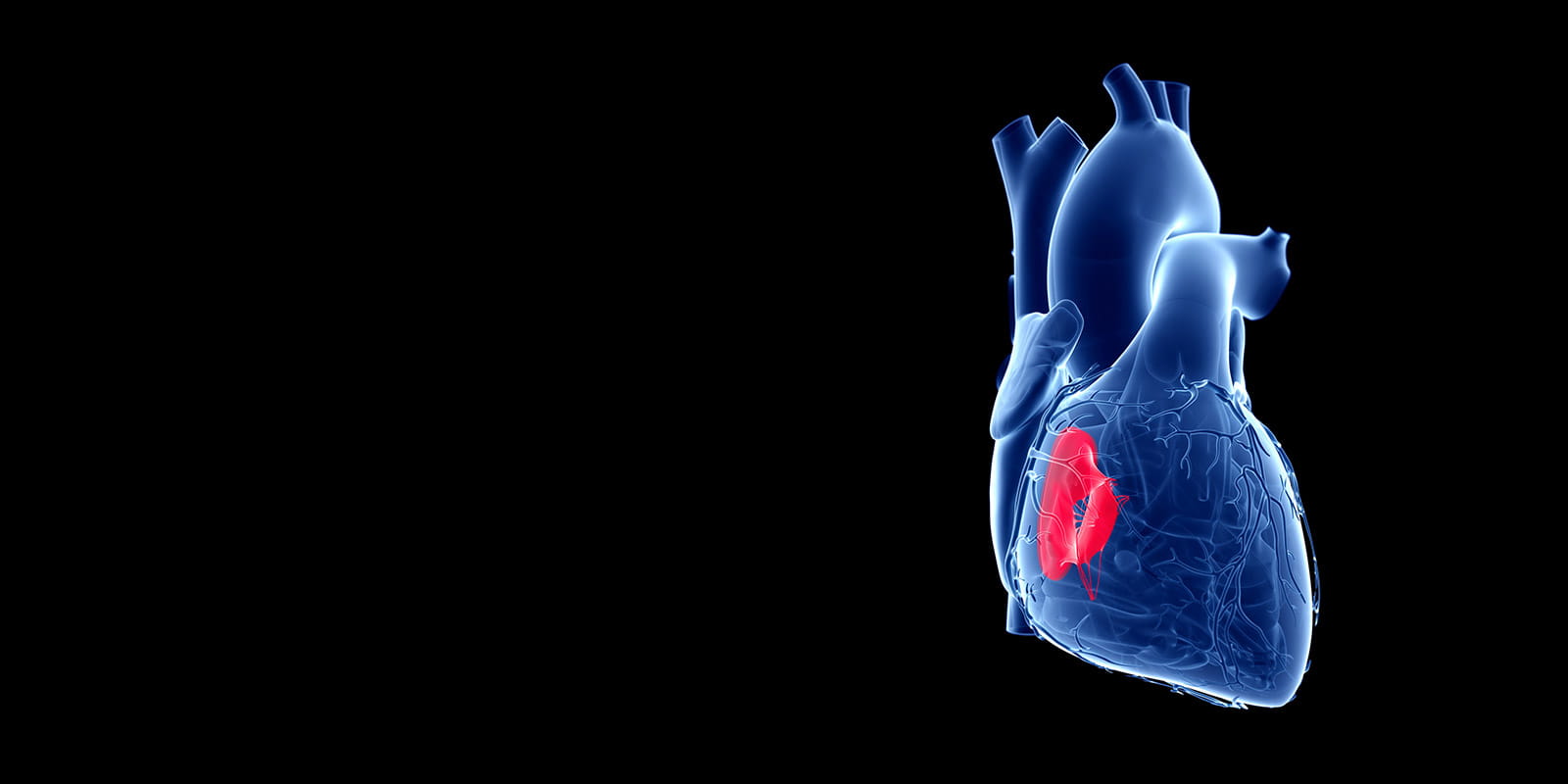

Tricuspid Valve Disease

Tricuspid valve disease is a form of heart valve disease. The tricuspid valve is one of the two main valves on the heart’s right side. A normal tricuspid valve consists of three flaps (leaflets) that open and close to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle while preventing blood from flowing backward. When the tricuspid valve does not function properly as a result of disease, the heart must work harder to send blood to the lungs and the rest of the body. Tricuspid valve disease often occurs with other heart valve issues.

Make an Appointment

Call 216-844-3800

Find a Heart Valve DoctorTreatments for Tricuspid Valve Disease

Tricuspid valve diseases treated at University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute’s Valve and Structural Heart Disease Center include:

Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation

In tricuspid valve regurgitation, the tricuspid valve doesn’t close properly, causing blood to leak backward into the upper right chamber (right atrium) of the heart. Some people are born with tricuspid valve regurgitation. Other times, the condition develops in connection with other heart valve problems.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation often does not cause signs or symptoms until the condition is severe. The condition may be discovered when tests are done for other reasons.

Symptoms of Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation

People with tricuspid valve regurgitation may experience some combination of the following symptoms:

- Fatigue

- Irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias)

- Pulsation in the neck

- Shortness of breath with activity

- Swelling in the abdomen, legs or neck veins

Causes of Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation

Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation can be caused by:

- Congenital heart defects (present at birth): Certain congenital heart defects can affect the functioning and shape of the tricuspid valve. Tricuspid valve regurgitation in children is typically caused by Ebstein’s anomaly, a rare congenital heart defect in which the tricuspid valve is malformed and sits abnormally low in the right ventricle.

- Bacterial infections: Untreated bacterial infections can cause rheumatic fever, which may damage the heart’s valves. When regurgitation and stenosis of the tricuspid valve are both identified, it’s usually due to this reason.

- Connective tissue disorders: Genetic diseases such as Marfan syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis are strongly connected to tricuspid regurgitation.

- Carcinoid syndrome: In this rare condition, tumors that develop in the digestive system and spread to the liver or lymph nodes secrete a hormone-like substance that can damage heart valves, most often the tricuspid valve and pulmonary valve.

- Endocarditis: Endocarditis is an inflammation of the interior lining of the heart caused by infection. People are at a higher risk for endocarditis if they require regular dialysis or have a permanent port implanted for intravenous (IV) medications.

- Myxomatous degeneration: This condition happens when the valve’s leaflets stretch too much, preventing them from sealing properly. More common in the mitral valve, myxomatous degeneration can also develop in the tricuspid valve.

- Other heart valve diseases or conditions: Any condition or disease that affects blood flow through the heart could potentially lead to tricuspid regurgitation.

- Chest injury (trauma): Chest trauma, such as that sustained in a car accident, can cause damage that leads to tricuspid valve regurgitation.

- Implanted devices: Tricuspid valve regurgitation can occur during the removal or placement of pacemaker or defibrillator wires that cross the tricuspid valve.

- Radiation therapy: Receiving radiation to the chest may damage the tricuspid valve and lead to tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Diagnosis of Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation

Certain tests can help diagnose tricuspid regurgitation, either on its own or in association with another disease or condition. Your primary care provider or a cardiologist may order one or more of the following:

- Physical exam: The physical exam will include listening to your heart and breathing sounds. A heart murmur can be easily detected during the physical exam. The doctor may also feel your neck and abdomen near your liver; a strong pulse in either location is a symptom of tricuspid regurgitation.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): A test that assesses heart rhythm.

- Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray uses a very small amount of radiation to produce pictures of the inside of the chest. The test can often reveal changes in the structure of the heart caused by tricuspid regurgitation.

- Echocardiogram: This test uses sound waves to create video images of your heart in motion to evaluate valve function, heart anatomy and blood flow through the heart. The test allows your doctor to see if blood is flowing backward inside your heart and to measure the severity of the condition

- Cardiac catheterization: A doctor inserts a small device into one of the arteries in your body, typically in your arm or in the groin area, and then guides it up to your heart. This lets the doctor to see and diagnose problems from inside your heart.

- Blood tests: Certain blood tests can detect a negative effect of tricuspid regurgitation on the liver.

Treatment of Tricuspid Valve Regurgitation

Treatment for tricuspid valve regurgitation depends on the cause and severity of the condition. Goals of treatment are to:

- Improve symptoms

- Prevent complications

- Improve quality of life

If a patient’s tricuspid valve disease is due to an underlying condition or congenital heart defect, they may need medications, a catheter procedure, or surgery to repair or replace the valve.

Medication

Your doctor may prescribe medication to manage symptoms or to treat the underlying condition that caused tricuspid regurgitation. Medications may include:

- Diuretics (drugs to remove extra fluids from the body)

- Anti-arrhythmics (drugs to control irregular heartbeats)

- Other drugs to treat or control heart failure

Valve Repair

Tricuspid valve disease is usually done in in one of two ways:

- Surgically: The surgeon makes an incision in your chest to access your heart directly and repair the tricuspid valve. Using minimally invasive techniques or robot-assisted surgery, this surgery can be performed through smaller incisions.

- Catheter-based procedure: Similar to the cardiac catheterization diagnostic procedure, a cardiologist can access the heart via a catheter (threaded to your heart through the vein at the top of your thigh) and attach a clip to the valve’s leaflets to help them seal correctly.

Valve Replacement

Tricuspid valve replacement is generally done in one of two ways:

- Surgically: This method is similar to the repair approach described above, except that the surgeon replaces the valve instead of repairing it. Types of replacement valves used include biological (humans, pig or cow), mechanical or a combination of the two.

- Catheter-based procedure: A cardiologist accesses your heart by navigating a catheter through the vein at the top of your thigh. Once inside, the defective tricuspid valve is removed and replaced with a new one.

Tricuspid Atresia

Tricuspid atresia is a congenital heart defect (present at birth) in which the tricuspid valve has not formed. Instead, a sheet of solid tissue blocks the flow of blood from the right atrium to the right ventricle, causing the right ventricle to be underdeveloped. A baby, child or adult with tricuspid atresia is unable to get enough oxygen throughout the body. People with tricuspid atresia tire easily, are frequently short of breath and may have blue-tinged skin.

Tricuspid Atresia in Adults

Adults with tricuspid atresia need to be seen regularly throughout their lives by a cardiologist trained in adult congenital heart conditions. An adult patient’s cariologist can recommend tests to evaluate the condition at these appointments. Sometimes, the cardiologist may recommend adults with tricuspid atresia take preventive antibiotics prior to having certain dental or medical procedures in order to prevent infective endocarditis.

Tricuspid Valve Stenosis

Tricuspid valve stenosis, also called tricuspid stenosis, is a narrowing in the heart’s tricuspid valve. As a result, it’s harder for blood to flow from the upper right heart chamber (right atrium) to the lower right heart chamber (right ventricle). If left untreated, the right atrium can enlarge and negatively affect the blood flow in the chambers and veins of the heart.

Risk Factors for Tricuspid Valve Stenosis

Rheumatic fever, a condition that develops from untreated strep throat, is the most common cause of tricuspid valve stenosis. Tricuspid valve stenosis can also happen during fetal development as a congenital heart defect, though that is rare. Sometimes, certain tumors or connective tissue disorders can lead to tricuspid valve stenosis.

Conditions that increase the likelihood of developing tricuspid valve stenosis include:

- Rheumatic fever: if you had rheumatic fever as a child, you more at risk for developing tricuspid stenosis.

- Congenital heart disease: For example, Ebstein’s anomaly is a rare congenital heart defect in which the tricuspid valve is malformed and sits abnormally low in the right ventricle. If a child has Ebstein’s anomaly, he or she is at greater risk of developing tricuspid valve stenosis.

- Other heart conditions: Heart failure, heart attack, pulmonary hypertension and other heart diseases put people at higher risk for developing tricuspid valve stenosis later in life.

Symptoms of Tricuspid Valve Stenosis

The most commonly experienced symptoms of tricuspid valve stenosis are an irregular heartbeat and a fluttering discomfort in the neck. Other symptoms may include:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath during activity

- Cold skin

- Enlarged liver

Diagnosis of Tricuspid Valve Stenosis

Your doctor can diagnose tricuspid valve stenosis during a physical exam. With a stethoscope, he or she may be able to hear a specific heart murmur associated with tricuspid valve stenosis. Other tests used to confirm diagnosis include:

- Echocardiogram: This test uses sound waves to create video images of your heart in motion to evaluate valve function, anatomy and blood flow through the heart. The test allows your doctor to see blood flowing backward inside your heart and measure the severity of the condition. It is the most common test used to confirm diagnosis of tricuspid stenosis.

- Electrocardiogram: This test can detect abnormalities heart rhythms, which can by a sign of tricuspid valve stenosis.

- Chest X-ray: X-ray images taken of the heart can help identify the presence of heart abnormalities, including those associates with tricuspid valve stenosis.

Treatment of Tricuspid Valve Stenosis

If your tricuspid valve stenosis is mild to moderate, monitoring of the condition without treatment may be sufficient. If you have tricuspid stenosis in combination with other severe valve stenosis, these conditions usually need to be treated with surgical valve repair or replacement. Surgical treatments for tricuspid stenosis include:

- Balloon valvuloplasty: During a balloon valvuloplasty, a catheter fitted with a deflated balloon on the end is navigated through the body to the defective tricuspid valve. Once in position, the balloon is inflated to widen the valve.

- Tricuspid valve replacement: In more severe cases of tricuspid valve stenosis, your doctor will recommend replacing the damaged tricuspid valve with a tissue or mechanical valve.

Ebstein’s Anomaly

In this congenital heart defect (present at birth), the tricuspid valve is in the wrong position, and the valve’s flaps (leaflets) are abnormally shaped. As a result, the valve does not function properly. The condition can cause blood to leak back through the valve, causing the heart to work less efficiently. Ebstein’s anomaly can also lead to enlargement of the heart and heart failure.

Adults With Ebstein’s Anomaly

When Ebstein’s anomaly is severe, it is generally diagnosed at birth or in the first months of life. Immediate treatment of the condition is required when it is discovered this early in life.

When Ebstein’s anomaly is diagnosed in adults, the defect and its symptoms are typically less severe. Ebstein’s anomaly can be mild during childhood but then worsen over time, causing symptoms later on. In adults, the most common symptoms of Ebstein’s anomaly include:

- Shortness of breath

- Occasional chest pain

- Becoming winded easily during exercise

- Heart rhythm disturbances (arrhythmias)

Adults with Ebstein’s anomaly should have regular appointments with a cardiologist that specializes in adult congenital heart defects. The cariologist will use certain tests to monitor the patient’s heart’s size, pumping ability and rhythm. These tests include:

- Electrocardiogram

- Chest X-rays

- Echocardiograms

Treatment of Adults with Ebstein’s Anomaly

Adults with a mild Ebstein’s malformation may not need treatment for years. For those patients who have an arrhythmia, the arrhythmia may need to be treated with medication or, depending on its severity, a nonsurgical treatment such as radiofrequency ablation. Adults with a Ebstein’s malformation who develop heart failure may require other medications, including diuretics (drugs to remove extra fluids from the body.)

If an adult patient’s Ebstein’s anomaly worsens to the point where symptoms are bothersome or the patient’s heart could enlarge, surgical treatment may be recommended.

Surgical procedures used to treat Ebstein’s anomaly include:

- Repair or replacement of the tricuspid valve: The goal of this surgery is to fix or replace the defective tricuspid valve so that the valve’s leaflets open and close normally. When enough tissue is present, the valve can be repaired. Valve repair is the preferred treatment because it uses the patient’s own tissue. If the defective valve cannot be repaired, it can usually be replaced with a mechanical valve or a valve made from biologic tissue. Patients who receive a mechanical valve replacement need to take blood-thinning medication for the rest of their life.

- Atrial septal defect repair: People with Ebstein’s anomaly often have a hole in the septum (the tissue between the heart’s upper chambers. This hole will be surgically closed at the same time the valve is repaired or replaced.

Make an Appointment

Call 216-844-3800